We. The few, the proud, the plodding.

Steven Pinker, in “The Language Instinct“, suggests that if language didn’t exist, people would be so driven to communicate that they would create a language. So strong is our instinct toward communication that there are almost no recorded instances of groups of people who have not developed a means of talking to one another.

Surely our ancestors had a running instinct as well. It’s hard to imagine a community of humans that would not have included runners. Some, though, then as now, were just a little slower than others.

The evidence of this instinct can be seen in children. Children seem content to simply run. Often they aren’t running to or from anything. They just run. For children, the act of running brings such pleasure that they don’t, or won’t, stop.

On the other hand, if you’re looking for a reason why some adults have lost the joy in their instinctive running, look no further than childhood. How many times are children told not to run? In how many paces are they not allowed to run?

Worse yet, for some children running becomes a form of punishment, as it did for me. In my high school, when you misbehaved in gym class, you were sentenced to run laps. Is it any wonder that my running instinct was buried?

When I am asked now why I started running after 40 years of sedentary confinement, I answer that running is in my genes. Somewhere in my genetic makeup is the DNA residue of great hunters and bold warriors and fleet messengers. When I dig deep enough into my soul, I am connected directly to those who ran for their lives.

I’m sure that great runners throughout history were revered for their skill and speed. I’m not convinced, though, that all of my running ancestors were gifted. I’m sure there were Penguins even then!

Had I been alive in prehistoric times, I suspect that the members of my tribe would not have selected me to chase down dinner. Given my ability to run, it’s far more likely that I would have ended up as some other animal’s dinner.

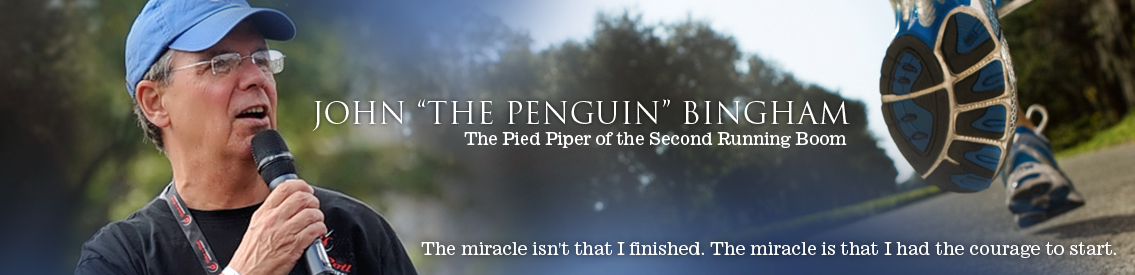

But my limited talent doesn’t mean I can’t, or shouldn’t, run. More importantly, it doesn’t mean that I’m not a runner. My terminal velocity relative to that of others of my age and gender is the result of the decisions I have made over the course of my life.

What is often misunderstood about those of us struggling to reach the front of the back of the pack is that we really are trying. We really are, at whatever our pace, doing the best we can. Some runners, and even well meaning non-runners, interpret our position in the pack as a measure of our effort. Nothing could be further from the truth.

We – the few, the proud, the plodding – very often train as much as, or more than, faster runners. At a blistering 12-minute pace, a 20-mile week represents a major time commitment. I do speed work and tempo runs. I do long, slow runs. I just do them very slowly.

It’s not a matter of trying. It’s not a matter of motivation. It’s just a matter of speed. A fast runner friend of mine put it succinctly when I asked him what he thought was the limiting factor in my running future. His answer was as insightful as it was concise: “Maybe you’re just slow!”

And slow I may be. But I am the best athlete I know how to be. I am the best runner I know how to be. Every day is an opportunity to improve. Every time I run, I try to be better. I have given in to my running instinct. I have given in to this passion to uncover the primal joy in running. And I hope you will, too.

Waddle on, friends.

Back to The Penguin Chronicles Archive

Thank you for this! It’s good to know that maybe I’m slow, just because I’m slow!